Fantasy: Utopian, Kind, Visionary?

Utopia not as a rigid blueprint, but as a dreamlike intuition, a hint, the tempting call of a wiser world… Can fantasy give us that?

With its vast old forests, the genre seems an obvious candidate for ecological utopias. But even for free and kind societies; after all, we can create anything. Fantasy doesn’t have to be bound to feudalism. And do we really need war, violence, and oppression just to be entertained? What if we could spend our evenings traveling through a world that embodies our deepest values?

A Call and a Quest

This essay is a call: to create more utopian, kind and visionary fantasy. But it’s also an invitation to explore: How would that even work? Can we write like that?

Utopia in Motion

A quick note on the term “utopia”: By that, I do not mean a fixed blueprint, not a society where everything is arranged perfectly and will never again need a change (that in itself would seem spookily rigid and even dystopian).

No, by utopia, I mean something that’s still open and flexible. I use the term as loosely as “dystopia”: We don’t call a novel “dystopian” only if everything in it is always and without exception terrible. Rather, it’s about the overall mood, the general situation. That’s how I would like to approach the concept of utopia as well.

And that on several levels.

Mostly Good?

Let’s begin by looking at the take on humanity we choose. Do we portray people as generally brutal, or as mostly kind? I like to think of Rutger Bregman’s book as bearing the title “Human-Kind”. It is a study on how surprisingly friendly and cooperative people in our world generally are—for instance, in the case of natural disasters. But also on other occasions: it happens far more often than one might suspect from watching movies or news reports.

So, what kind of characters will we make appear in our fantasy worlds? Ones who act at least as kindly and wisely as those documented real-world people? Perhaps even a little more so? And: How beautiful is the world? Do readers experience it as rich and precious and incredibly alive? How good is society? Are the structures as humane as even the best real-world examples? Or even better?

Novels are a wonderful way to breathe life into our visions. Political theories are great, but getting comfortable on the sofa and watching this attractive world rise before our eyes is something else entirely. The playful details, the vibrant characters, the colors and emotions—all of that brings a completely different power to the idea. Novels can be a very relaxed, yet highly effective way to dream our way into a desirable world, and perhaps even to slowly grow into it. After all, self-fulfilling prophecies can happen—in either direction.

The Future

But wait, aren’t visions of the future the domain of Science Fiction? Fantasy is often inspired by historical settings, and that makes visions of social progress a bit difficult to integrate, doesn’t it?

I believe we can free up our thinking about both the future and the past here.

Regarding the future: If Science Fiction is heavy on space travel, or at least heavy on high tech, then I strongly suggest it shouldn’t be the only genre where we imagine our future. Hyper-technological societies can be ONE vision for humanity, but please, certainly not the only one. We need broader horizons and more space for visions of the future. This could happen within Science Fiction, in sub-genres like Solarpunk. Or Science Fiction could be part of a larger Future Fiction, a field where vastly different roles for living nature, technological artifacts, and social wisdom are imagined. And perhaps even other genres can offer stories inspiring our human journey. Should Fantasy be one of them?

But in any case: let’s have more room for more futures.

The Past

So what about the past? Quite often, the portrayal of “history” in “history books” still follows a very narrow logic. As a result, our collective image of the past can be very limited, dominated by wars and kings in Europe. But there was much more to it.

For instance, throughout history and across various continents, we have seen a great deal of cooperation. In their non-fiction book “The Dawn of Everything”, David Graeber and David Wengrow open our eyes to how far the complexity of cultural life had already progressed 40,000 years ago, and how much diversity among societies existed.

Even much later, and even within feudal systems, many farming villages collectively managed commons, from pastures to forests and fishing grounds. This included complex social arrangements on who would use and contribute how much at which time. Even highly complex irrigation system were set up and managed successfully for centuries that way, all based on agreements among villagers. If we make these folks the center of our story, then cooperation, community and self-organization will automatically be a prominent feature.

As writers, we choose which part of human history we draw our inspiration from.

Furthermore, unlike historical fiction, fantasy actually calls on us to develop the tales from the past, to change and transform them and let the old seed bloom into a new, slightly different kind of blossom. We have leeway here, which we can use to build a vision.

But most importantly: Fantasy does not have to be based on history. We create worlds, and we can do it exactly the way we want to. Especially in High Fantasy, who says whether the elves—and indeed the humans—are governed by kings or by an eco-anarchic love of freedom? It’s up to us, the authors.

But… perhaps we don’t dare. Or we don’t know exactly how to do it.

Three Paths

Therefore, I would like to present a few prototypes for writing our way into utopian fantasy.

I’ll start with an example so old it is perhaps even a little boring. But precisely because we are all so familiar with it, I think it serves as a good point of comparison for discussing other, still unfamiliar themes.

So here is the well-known example: It’s about the presence—or absence—of female characters in fantasy novels.

There was a time when all fantasy heroes were male. At that time, there were also many explanations for why it couldn’t be any other way.

Then, a few women started walking by in the background of a novel and maybe even said a word or two! A ray of hope! Apart from that, the setting stayed exactly the same.

Eventually, a woman became the main character of the novel, and her rebellion against traditional roles was at the heart of the story.

That’s an explicit departure (within the fantasy world, but also, on a meta-level, for the genre).

And finally, there is fantasy where women are naturally found in all roles and positions in the world, and this is not even addressed because it is simply taken for granted. I would like to call this method a background utopia, placing it alongside the approaches of ray of hope and explicit departure.

Can we now use this to write utopian societies into fantasy? I will focus on two new aspects as examples:

Firstly: a society of people who are free, equal, and cooperative (instead of living with hierarchy, exploitation, or oppression, as we have often written into our worlds so far)

Secondly: a departure from murder and bloodshed

Ray of Hope

Let’s look at the ray of hope method first. This approach is excellent for feeling our way forward. As writers, even while we still don’t dare to truly overthrow old tropes, we can at least send out a small test balloon.

For instance, we might have a side character who questions warfare on a matter of principle, and actually refuses to take part. Or a small culture on the fringe of the novel might proclaim that everyone is equal in rights and dignity, and actually live that way too. That way old tropes get challenged even though they still dominate the rest of the book.

Fortunately, rays of hope can already be found in many places.

Don't hit, talk!

As an example, I will draw on The King’s Sword by C.J. Brightley. Much about this book is very conservative, and the main hero is, yet again, a warrior. But when hostile hordes cross the border on raiding sprees, he does not strike back. Instead, our hero figures out who these “hordes” actually are and what their situation is. The conclusion? The famine they are facing can be alleviated by reopening old trade routes that were closed due to past conflicts.

Win-win. Such a solution is wonderful, of course. But what I am really trying to get at here is the fundamental approach, the moment when the hero starts asking the right questions: “Who are these people? What do they want and need? How can a solution be found?” (Instead of just: “How do we kill them?”)

Here is an example from another novel, this time on a personal level:

In this scene, our hero is locked in a dungeon and desperately needs to get out to save the town. While imprisoned, he realizes he has a magical power: he can form and throw fireballs. Then the guard returns. And what does our hero do? He does NOT hurl a fireball in the guard’s face! Instead, he talks to him and addresses the situation from his perspective. He essentially says: “I know you’re not allowed to speak to prisoners, but please ask your captain if he will hear me out. It’s an urgent matter of saving the town.” And that is how it goes.

This is the same shift as above: Instead of fighting and killing, we try to understand the situation others are in, and propose something that is actually feasible for everyone involved.

I encounter this level of personal maturity quite often in the real world, but relatively rarely in fantasy characters. So far, they mostly seem to be very bad at talking, and very quick with brutality.

The scene, by the way, was from Matthias Teut in his first volume of Erellgorh, a book that by no means maintains that same approach throughout—but it could! And that is my plea. Let’s dare to do it! Many books have some rays of hope, and we could take them so much farther!

And it is definitely worth the while. Fantasy has great power. It reaches directly for the deep roots of our culture and nourishes the fundamental myths, strengthening them through constant retelling—or changing them.

Let’s be conscious of the choices we make here, and deliberate in what kinds of interactions we normalize, what we present as standard or as expected behavior.

Myths of Violence

War and violence are crucial in this regard. In this area, the real world draws very directly on deep roots and the cultural subconscious. It may be war propaganda invoking the hero myth, or a hoodlum feeling like the star of a movie poster whenever he turns violent.

Myths of violence can only be summoned up so quickly because they have been rehearsed a hundred times. They only carry so much power because they have been brought to life and charged with emotion over and over again. Fantasy plays a crucial role in this—for better or for worse.

So what’s our guideline?

As the absolute minimum, I would suggest we ensure that our novels do not pave the way for real-world brutality. That they do not glorify violence, neither in war nor in private settings, and do not provide subconscious templates for thrashing or slaughter.

That is the lowest bar. Beyond that, we can do much more. We could describe genuinely good ways of handling conflict, for example. There are many excellent communication handbooks and wisdom teachings, and the theories are great. But it would be wonderful if we could then observe people who actually live that way on an everyday basis. Let’s tell ourselves those stories!

Hard to write? Perhaps. But overall, it is much easier to write a wise person than to be a wise person. So I would hope that our fantasy is a little ahead of the real world, or at least not lagging behind.

Where is the Tension?

Very well. But even if we write such worlds: wouldn’t that be boring? If everyone is mature and wise, and society is fundamentally good, what is there to write about? Where does the tension come from, and what is the plot?

In response I would like to point to an experience some of us have already made in the real world. You may be working on a project with a group of committed people—and things go wrong all the time, leaving you buried in problems and conflicts, even though everyone is trying their best.

That can also happen in our fantasy worlds, on the personal as well as on the collective level. Others might still be a pain or at least an enigma to us.

But now the question the characters ask is no longer: “Who should we kill and how?”, which perhaps a classic court intrigue might still lead to. The new query is: “What could everyone live with?” This, I believe, is the more complex and interesting question anyway. And it allows for a wonderfully rich depiction of cultures, personalities, and conflicts of interests.

In such negotiation-driven novels, the need to avoid war might serve as a background element of tension. But even that is not necessary. We can also write a world where it is totally obvious to everyone that—problems or not—they certainly aren’t going to kill anyone. War is unthinkable in that world.

The Power of a Utopian Background

This brings us to the realm of background utopias: where positive aspects of society are normal reality. They don’t need to be argued or fought for, but can be taken for granted.

I believe this type of utopia to be extremely potent. It carries the normative power of the factual.

At the same time, it opens up particularly wide horizons. By remaining in the background, the utopian elements are less conspicuous. Thus they can more easily bypass the internal censor that often tries to stop authors from writing unusual and visionary stories.

Readers with different political views can also absorb these background utopias more easily, accepting them simply as a description of that specific setting. That’s just how things are in that world. No need to instantly quibble or object.

Impact

And no matter how we write our background: it always has an effect.

For this is how all socialization works: We see images, we hear stories, and our subconscious already extracts the patterns from them. This is how the building blocks of culture form in our minds. It’s how we learn what constitutes normal and expected behavior, or what a friendship, a marriage, or an oath means. The patterns of society develop within us, they deepen— or they change, depending on what we feed them.

Discourse analysis shows how the repetition of words and concepts makes certain things thinkable or unthinkable, how it fosters mental connections, and creates realities. For ultimately, that is what we do: We build reality. This society is made by humans. Culture is created. And we are right in the middle of it.

Manifestos and Realities

It is up to us to make old traditions evolve. Appeals to question existing tropes and habits are extremely helpful here, like the one Judith Vogt and James Sullivan made in 2020: “Let’s write progressive fantasy and science fiction!” Yes, let’s question existing tropes and habits.

In addition to encouraging appeals, we can also look at the real changes that have occurred in the genre. Much has happened, and these achievements should give us strength and courage for venturing further.

Let’s go back to the example I started out with: Female characters, even in leading roles, really don’t surprise anyone anymore. Yet it wasn’t so long ago that female leads were considered impossible, and a hundred arguments raised why it would not work. But it does. It works very well, actually.

A lot of progress has been made, especially regarding gender roles, women, and queer characters, but also concerning other levels of diversity, from looks and origin to specific physical and mental conditions. A lot is in flux right now in this area.

The Cozy Overthrow

I see another big success story in overturning genre traditions: cozy fantasy. “Cozy” first of all implies a feel-good atmosphere, and that in itself is not automatically progressive in social terms. But with this atmospheric shift alone, cozy fantasy has uprooted a fundamental belief that had become widespread: that fantasy must be dark. Grimness sells well, and there is no other way.

But there is another way. And cozies sell well too. Completely different moods and completely different plots are possible. The story now might revolve around solving a riddle or finding a treasure, perhaps like in some role-playing adventures. A ghost needs help finding its way to the afterlife. A crime calls for closure—and perhaps it wasn’t even a murder. Or maybe I quit my job and start a new life in a small-town coffee shop: slice-of-life.

There can be completely different sources of tension that bring a completely different logic to the plot. But classic political themes of saving the world are also possible.

Cozy fantasy is an open field for utopian visions. It offers so much that could only be reached with great effort coming from grim darkness. With cozies, readers are already open to good moods and good news. And even to good worlds. Let’s give it to them! Lots of good worlds, with lots of variation!

Political Opposition

Speaking of variation and difference: there is another reason I referred to C.J. Brightley above. For she also issued a call: “Let’s write another kind of fantasy!” The term she uses is “noblebright”, in contrast to “grimdark.” Her personal slogan is “Fantasy to believe in”, and I love that. What a wonderful motto, I thought, and began to find out more about her and her background. And at some point, my jaw dropped. My impression was that I had landed among conservative Christians in the US, whose day jobs were with the Army or the CIA.

That is not my usual political corner.

These differences are also reflected in our respective novels. Well, I thought, perhaps it would be a refreshing innovation in the political debate if we presented each other with our utopias? Up until now, we have often depicted how terrible and dystopian everything will be if the awful Others gain power. How about we tell each other what a good world looks like? Let’s hold our dreams up for mutual inspection! That would move the debate to an entirely different level. And right now, the political discourse might indeed benefit from a new, playful element.

Background without Blueprint?

But then, if I am to paint this picture of my utopian society into the background of my novel: How would I do that, if maybe I don’t even know exactly what all the details of that would look like? And if I do know the details: Wouldn’t that bring me back to the fixed blueprint I wanted to avoid?

I believe it can work just fine. We can playfully paint a picture without falling into rigid perfectionism. Because with a utopian background, things can remain vague. For example, readers may understand that in this fantasy world, decisions are made by the community. But exactly how that works—that can be described in detail if the author so chooses, or it can just be hinted at, prompting the reader to dream up the rest.

Or there may be a society in which goods are distributed in a way that ensures everyone has enough. As readers, we see no poverty, and we see one or two concrete scenes of redistribution. But whether the distribution always works exactly as it did in that one scene, or what that other mechanism the characters mentioned in passing was: much can be left open. And yet, the general direction is set, and the imagination inspired by hints and examples.

Freedom of Choice

In closing, I would like to say that I definitely see a space for warning dystopias. Depicting painful struggles can also be important so that we feel seen in our own suffering.

It is a balancing act: Where is looking into the abyss helpful, and where do we only plunge ourselves into destruction with self-fulfilling prophecies, or simply wallow endlessly in our pain?

I think the answers to this depend very much on context, and I would like to let everyone decide for themselves what it is they need right now.

But at the moment, they cannot make that choice. Because there is far too little utopian content. We have a huge mountain of dark and dystopian material, but where is the equally large mountain of various visions and inspirations? People-friendly societies are still few and far between in the fantasy realm. Even mature, peaceful characters who patiently work toward the well-being of all are relatively rare.

But I’d like to be able to choose which images I feed my subconscious right before going to sleep.

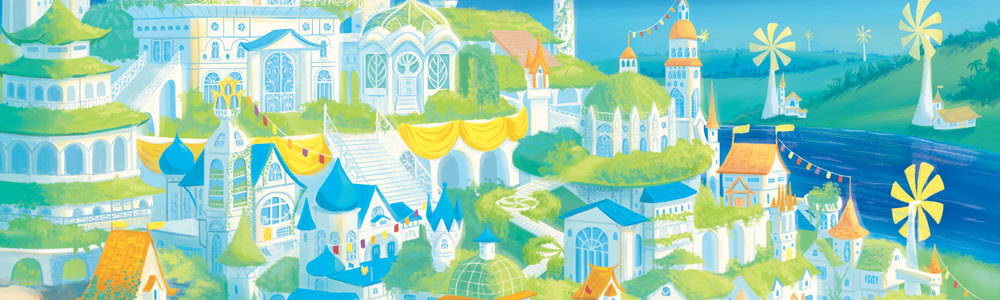

So, let us create this missing ecosystem! Where many different versions of a good world can flourish side-by-side, featuring the most varied stories and writing styles. Only when these landscapes exist do readers truly have a choice. Let us give them this freedom! And ourselves as well.

Therefore, please: Let’s write lots of kind, inspiring and utopian fantasy!

And: Let’s talk about it! I look forward to hearing from readers and writers. Let’s stay in touch, as a loose community of interested people, where some of us can venture to meet the devils in the details and tell those tales…

PS. This article is based on a talk I gave on October 18th, 2025 at the BuCon accompanying the Frankfurt Book Fair. Thanks again for the invitation and the vivid interest! 🙂

November 2, 2025

Born Free and Equal: Writing Convivial Fantasy Worlds

A fantasy world self-organized in vibrant relationships and cooperative convivial structures

November 2, 2025

Crime Stories with a Heart: What if Healing Came First?

What if healing and reparations were our main response to the hurt that crimes cause?